Essential Components Weightlifting Technique:

Part IV

More About the Jerk

Andrew Charniga, Jr.

Sportivny Press©

Livonia, Michigan

2005

The Inter Muscular Coordination of the Muscles of the Upper and Lower Extremities and the Technique of the Jerk

“The muscles in the kinematic chain are included in the work in an appropriate sequence which enables them to sequentially express their functional qualities (ability for powerful force and speed of contraction) during the course of the movement.” (Y.V. Verkhoshansky, 1977)

One of the most important elements of sport technique is the appropriate sequential distribution of work between the weaker and the strongest muscles involved in the exercise. It is widely accepted that an athlete should begin a sport exercise with the strongest muscles and finish with the weakest.

The “weaker” muscles which actively take part in the weightlifting exercises should come into play in such a way as to compliment the forces produced by the muscles of the trunk and lower extremities; they are not to “dampen” or inhibit them. According to Luchkin, “the weaker muscles should be included in the work at full force at such an instant that their force is combined with that produced by the other muscles to yield the greatest effect, i.e., contribute to a large increase in barbell speed.” (8)

If a lifter “waits” until the legs have fully straightened from the recovery from the half squat in the jerk before employing the arms, and this sounds entirely logical, it is already too late. Even before reaching this juncture in the lift, the force potential of the legs is already at the point of diminishing returns. So, the arms need to come into play in the jerk sooner than contemporary thinking could possibly anticipate. (8)

Furthermore, the role of the muscles of the upper extremities should not be to lift the barbell through pressing upward in the jerk. The action of pressing the barbell in the jerk comes at the expense of the full potential of the muscles of the lower extremities. The use of the muscles of the upper extremities to lift the barbell in the jerk dampens the force of the legs to rearrange the feet into the spilt position.

The Effect of Pressing Exercises on the Jerk

“The jerk should be executed first and foremost by the legs.” (L.N. Sokolov, 1963) {44}

More than 40 years ago, Luchkin (8) described the correct sequence of including the muscles of the upper extremities in the jerk, which, on the surface, appears to be, at best, illogical. “The arms should come into play before the legs have fully straightened, before the instant of barbell separation from the chest.” This does not mean the lifter begins “pressing” the barbell up with the knees still bent and then splits under it in the jerk.

The fact of the matter is that the lifter should not try to press the barbell in the jerk at all because pressing it involves lifting it with the arms and shoulders. One should use the arms and shoulders to push the trunk away from the barbell, i.e., to push the lifter into the split or half squat position (2,8,20,24,41). The kinetic energy of the descending body is transmitted to the barbell through the pressure of the hands on the bar (40,45).

The Biomechanics of Pressing

Essentially, the mechanical leverage of the muscles employed in the military press exercise varies according to the position of the barbell, the hand spacing, the method of grasping the bar, the disposition of the elbows, and the disposition of the head (58). The greatest force potential occurs at the beginning of the movement with the weight still on the chest i.e., the pressing muscles are at their greatest length. The favorable mechanical leverage diminishes quickly after the barbell separates from the chest. It begins to improve slightly as the barbell passes over the head, but the favorable leverage conditions never return as the movement is completed (2,8,15,8).

The beginning of the military press is easier than the middle or the end of the exercise because of the varying biomechanical advantages which occur throughout the movement. It is natural for the lifter to endeavor to use the favorable mechanical conditions of the start by trying to impart as much speed on the barbell as possible at the beginning of the exercise. An explosive start will allow the lifter to use inertia to facilitate the barbell’s movement through the mechanically more difficult positions.

The athlete essentially lifts the barbell from the chest to arms length overhead in the military press with the strength of the arms and shoulder girdle while maintaining a relatively fixed position of the trunk. This is true of any form of strict pressing because the muscles of the arms and shoulders (and chest muscles in bench pressing) lift the barbell by overcoming the varying mechanical leverages solely by muscular force.

In the jerk the lifter should employ the favorable leverage of the pressing muscles to “push off” from the barbell at the beginning of the descent, coordinated with the rearranging of the feet. The actual lifting of the barbell with the arms comes from the pressure of the hands on the bar transmitting the kinetic energy of the body to the barbell. The lifter follows the path of least resistance for the arms by pushing the body away from the barbell, i.e., the trunk moves away from the bar as the mechanical leverage of the pressing muscles improves. The fixing of the barbell on straight arms is coordinated with the feet returning to the platform so that the support reaction is transmitted to the barbell most effectively.

Therefore, the biomechanics of the muscular force involved in strict pressing movements is quite different from the correct biomechanics with which the pressing muscles are deployed in the jerk. In the former, the pressing muscles move the barbell against a fixed trunk or support; whereas, in the latter, the pressing muscles move the trunk away from the barbell, i.e., follow the path of least resistance.

The Effect of Pressing on the Technique of the Jerk

Strict pressing exercises such as the military press, bench and incline presses essentially involve lifting the barbell from the shoulders or chest to straight arms with the trunk fixed or against a rigid support. The muscles of the arms, shoulders, and chest do all of the lifting. The lifter is unable to avoid the unfavorable leverage the pressing muscles encounter in the middle of the exercises, commonly referred to as the “sticking point” because the trunk is stationary. There is no other alternative way of moving the mass. The body does not have to “think.”

The slow muscular contraction involved in strict pressing heavy weights is very close to isometric conditions. High muscle tonus can occur as a result of excessive or frequent use of isometrics (or what is essentially an isometric contraction when one presses or deadlifts a heavy weight). High muscle tonus is known to manifest a negative carry – over to the speed strength exercises: the snatch and the clean and jerk. There is a direct connection between the use isometric exercises and high muscle tonus (19,20, 53).

Research of the press era established that “weightlifters who are good pressers have significantly higher muscle tonus than those who have high results in the tempo exercises” (L.N. Sokolov, N.A. Yaroka, 1968). A high muscle tonus has a negative affect on the muscles’ ability to relax quickly, which, in turn, adversely affects speed of movement.

A weightlifter develops a specific motor habit with respect to the use of the muscles of the upper extremities in strict pressing exercises. This pattern is radically different from how these muscles are used in the correct technique of the jerk. The correct technique of the jerk involves using the arms to push the trunk away from the barbell instead of actually lifting it with the arms and shoulders.

Therefore, one should exercise caution in the selection of assistance exercises for the jerk. An important consideration in determining the value of the assistance work for the jerk is the motor habit developed.

A weightlifter lifts significantly more weight in the jerk than could possibly be raised over head solely with the muscles of the arms and shoulder girdle i.e., without the use of the legs. The muscles of the upper extremities have to work in harmony with those of the lower extremities in such a way as to compliment or facilitate each other. It has already been indicated that strict pressing involves a different motor pattern for the arms and shoulders than what is involved in the correct technique of the jerk. Consequently, one has to exercise some caution not to get carried away with these exercises.

On the other hand an exercise like the “push press” would seem to be very helpful for the jerk. In this exercise the lifter bends and straightens the legs quickly, then lifts the weight to arms length after the legs have straightened. The lifter finishes lifting the barbell to arms length by pressing on the barbell with the legs straight and the trunk in a fixed vertical position. The barbell’s inertia generated from the leg facilitates the work of the arms and shoulders.

However, the push – press is probably one of the worst, if not the worst, assistance exercise for the jerk. The motor pattern one develops from this exercise may result in a negative transfer of motor habits to the technique of the jerk; it may be worse than one might suffer from too much strict pressing. The coordination structure of this exercise is the antithesis of how the muscles of the upper and lower extremities in the jerk should be deployed in the jerk.

A weightlifter learns to consciously straighten the legs fully to execute the push – press. This is an incorrect habit because a weightlifter should have begun switching directions from lifting to descending while the knees are still flexed. There is no instantaneous switching of directions from lifting to descending in the push – press. Consequently, the arms and shoulders “press” the barbell up with the assistance of the leg drive instead of pushing the trunk away from the barbell, i.e., the body does not “think” to follow the path of least resistance.

A study of commonly employed exercises for the jerk undertaken by Ivanov (cited by Khairullin {57}) reported that after the elimination of the press, many Soviet lifters employed the push – press as an assistance exercise. Overall there was a negative affect on the jerk. Subsequently, the push – jerk became a popular assistance exercise. But this exercise can also exert a negative affect on the jerk (57).

Strange as it may seem, the technique of the “Olympic” press which evolved in the late 60s and early 70s just before it was eliminated from competition had more in common with the technique of the jerk than either the push press or any form of strict pressing.

In fact, a world record holder who had good technique in this version of the press, (also called the “tempo” press) typically was not the one with the strongest arms and shoulder girdle.

The technique of the “Olympic” press was similar to the jerk except the feet had to remain in the same place. It began with a preliminary quick shifting of the trunk down then up, which included a little “bowing” of the knees. This served to produce a powerful lift off from the shoulders because this movement was coordinated with the quick bending of the bar.

In the next instant, the lifter would quickly push his trunk in a backwards lean away from the barbell with the arms and shoulders. This quick “backbend” when coordinated with the starting motion allowed the lifter to avoid the “sticking” point one encounters in strict pressing by pushing the trunk away from the barbell. This backbend also activated more muscles, albeit briefly, to participate in the “pressing”, i.e., the work of pressing was distributed between the muscles of the arms, shoulders, chest, and torso.

Furthermore, the lifter actively coordinates and, consequently, combines the reactive forces of the quick stretching of the muscles with the bending of the bar.

So, the coordination structure of the old “Olympic Press” as it was called had more in common with the jerk than a strict press or even a push – press. But, this is not to say by any means that one should practice the old “Olympic Press” to improve the jerk.

To be of any real value, the coordination structure of assistance exercises for the jerk such as pressing movements need to be as close as possible to the coordination structure of the jerk, especially with regards to the correct relative contribution of the muscles of the upper and lower extremities. Otherwise the weightlifter risks doing more harm than good.

The Connection Between the Technique of the Jerk and the Strength of the Upper Extremities

Years before the birth of the famous American architect Frank Lloyd Wright, Frederick Engels wrote of the harmony to be found in nature between form and function (14). The biomechanical specifics of the weightlifting exercises require a harmonious development of physical qualities such as strength, speed, and flexibility. This is also true of the relative strength between the different muscle groups which are directly involved in the lifting of the barbell.

The physical development of today’s best lifters is a bit different from those of the not so distant past. The muscular development of the lifter’s body is a reflection of the modern technique of lifting and the modern contents of the training. Many of today’s best lifters have an almost pear shape development. The size and the relative strength of the muscles of the upper extremities of today’s best lifters have receded, relative to those of the lower.

The strength ratio between the muscles of the upper and lower extremities has special significance for the jerk. The strength of the arms and shoulders is obviously an important element of the jerk because weightlifters have lifted more than three times bodyweight and the barbell has to be secured at arms length overhead. However, there is a direct connection between the optimum technique of the jerk and the relative contribution of the arms in the actual lifting of the barbell

Since one lifts the barbell in the jerk with a combined effort of the legs, arms, and shoulder girdle, it is logical to assume that the stronger the weightlifter’s arms and shoulders, and the stronger the legs, the more one can jerk. But, this is not necessarily true.

Some research near the end of the press era investigated the connection between the “aging” Soviet national team their lagging results in the snatch and the clean and jerk and the rate of improvement of the press.

One study (52) looked at the interrelationship between the strength of the arms and shoulder girdle and the extensor muscles of the legs and trunk. The strength test results between two groups were compared: those who excelled in the press and those who excelled in the quick lifts. The good pressers were found to have a ratio of arm and shoulder strength to extensor strength of the legs and trunk of 52.3%. The ratio between these same muscle groups was 40.7% for the lifters who excelled in the quick lifts.

The author determined that the optimum interrelationship of 40.7% between the strength of these muscle groups should be found with the lifters who were good in the quick lifts. He recommended this strength interrelationship should be a point of orientation for the new biathlon era of weightlifting (7, 52).

Even before the press was eliminated and subsequent to its elimination, considerable discussion and some experimental research was devoted to determining the appropriate volume of pressing exercises for the weightlifter’s training in the biathlon. R.A. Roman recommended a volume of 10% of the total volume of lifts be devoted to pressing exercises (48).

One such study found that reducing the volume of presses from 20% to 10% resulted in greater improvement for the clean and jerk than the snatch (56). Therefore, a reduction of the volume of presses from as high as 40% of all lifts in training during the three lift era to 10% did not “weaken” the lifter for the jerk, as some feared. On the contrary, the lifters experienced a disproportionate improvement in this exercise by allowing the strength and size of the pressing muscles to “deteriorate” a bit.

L.N. Sokolov (44) was one of the first weightlifting bio – mechanists to employ a force platform to study the technique of the weightlifting exercises. He observed a sharp drop in the support reaction when the lifters they studied included the arms in the jerk too soon. The athletes who were good in the press were most likely to use the arms too soon and consequently “cancel” some of the force generated by the legs. “Those who are good pressers try to accentuate the muscles of the arms and shoulder girdle in the thrust phase of the jerk. This causes a sharp reduction of force from the legs; this is the principal reason the weightlifters who are good in the press perform the jerk poorly” L.N. Sokolov, 1965 (52).

Curiously enough, Sokolov discovered the same circumstances in the pull segment of the clean. The strong pressers began to include the arms too soon in lifting the barbell which caused a noticeable drop in the vertical force produced by the strongest muscles of the legs and trunk (44). The nervous system receives and reacts to the information relayed from the muscle and joint sensors that the weaker muscles of the arms are “between a rock and a hard place,” i.e., the arms form the weak link between the vertical force generated by the legs and trunk.

This study revealed but did not mention an interesting circumstance. In the case where the arms come into play too soon during the pull phase of lifting, it is curious that even though it is the extensor muscles of the shoulders and arms which are the “overdeveloped” muscle groups (the good pressers), the arm and shoulder flexors still “get in the way.”

The nervous system reacts to the too early inclusion into the work of the weaker muscles of the arms and shoulder girdle at an inopportune instant of the lifting. As a result, the strongest muscles are inhibited from developing maximum force because the nervous system senses they are working in opposition to the weaker in directing force against the support (52).

There is a significant drop in the support reaction when this occurs in both the pull and jerk phases of lifting. “Even a small shortening of the aforementioned muscles, which is not always visible to the naked eye, causes a significant drop in the force developed by the extensors of the legs and trunk” (44).

Apparently, if the athlete is in the midst of lifting a big weight and has a loaded cannon (strong arms and shoulders) at his disposal, it can go off whether he wants it to or not.

Sorokin (45) also determined that there was a negative affect associated with getting carried away with developing the press. “An attempt to develop excessively one of the qualities leads to a suppression of the other qualities, especially the motor activities by disrupting their most effective interconnection and lowering sport results” (Korobkov, 1958).

According to Sokolov, “relatively weak muscles of the arms and shoulder girdle noticeably facilitate the assimilation of the technique of the snatch and the clean and jerk. This is because the strength developed is in accordance with the necessary physical qualities of the sport technique” (19).

Research shows that one would expect those lifters who are (relatively speaking) disproportionately “weaker” in the arms and shoulder girdle to be better at the jerk than in the opposite case. These athletes would be forced to rely principally on the reactive and explosive strength of the legs to lift the barbell. Therefore, the only logical way to develop the technique of the jerk is to focus on developing the reactive and explosive strength of the legs.

This is a concept difficult to grasp because it is logical to assume that the stronger the arms and shoulder girdle the better; however, a weightlifter lifts the barbell in the jerk with a coordinated effort from the upper and lower extremities.

According to the literature and anecdotal evidence, the strength of the upper extremities can reach a level where it impedes the optimum distribution of work between the muscles of the lower and upper extremities. Significant strength of upper extremities, relative to that of the lower extremities, becomes a point of not only diminishing returns, but it is, in actuality, a hindrance to the correct technique of the jerk and, subsequently, improvement in this exercise.

Furthermore, the methods typically employed to significantly increase the strength of the upper extremities involve lifting large weights. This means the contraction of the muscles is rather slow and there is no rapid switching from contraction to relaxation between muscle antagonists. Consequently, the nervous system is being “tuned” for the wrong type of neuro – muscular activity.

It is not a simple matter to subordinate the “unnecessary” participation of the upper extremities during the jerk. The lifter can deploy these muscles where his action does not contribute to the force developed by the legs. The lifter may be imperceptibly trying to lift the barbell with arms instead of pushing away from the barbell.

The significance of the strength of the arms and shoulders illustrates what Engels said about the harmony in nature between form and function. The arms and shoulders are not designed to play a major role in lifting a big weight in the jerk. In order to lift a big weight overhead that is well beyond the strength of the arms and shoulders to overcome, the legs have to play the main role. Therefore, the physical development of the modern weightlifter is a reflection of the relative contribution of the relevant muscle groups to the technique of the jerk.

A weightlifter is better able to learn the appropriate contribution of work from the arms and shoulders to a technically efficient jerk when the arms are (relatively speaking) weak and not vice versa. This is the main reason someone who has first trained for powerlifting (and developed a high level of arm and shoulder strength), for instance, has difficulty learning the jerk. These athletes have difficulty learning how to most effectively use the legs and to subordinate the role of their too – strong – pressing muscles.

The development of today’s successful weightlifters is in conformity with the harmony between form and function. The role of the pressing muscles of today’s most successful weightlifters is a reflection of their development; it is secondary. The technique of the jerk, like that of the clean and snatch, reflects the contents of the modern weightlifter’s training. The use of various assistance exercises for the jerk, such as presses and push – presses and the strengthening of the upper extremities outside some reasonable proportion to the lower extremities, can create problems in the realization of one’s potential in the jerk.

It is necessary to understand that in learning, perfecting, and training an extraordinarily complex exercise like the jerk, as the saying goes, is “all but impossible to separate form and content.”

The Theory and Practice of the Jerk

High class weightlifters frequently miss jerks in international competitions (38, 40, 57). Roman and Ivanov reported that 20% of the lifters zeroed in the clean and jerk by missing all of their jerks; and, the success rate of the jerk was only 50% for lifters in Soviet National Championships and other major events (40). The jerk segment of the clean and jerk is an extraordinarily complex exercise and the success rate with near – maximum and maximum weights is rather low.

The “reactive strength” of the lower extremities has enormous significance for the jerk. Excessive strengthening of the muscles of the upper extremities can have a negative effect on the technique of the jerk. The weightlifter has to be cautious not to get carried away with the development of “subordinate” physical qualities such as the absolute strength of the upper extremities.

Not infrequently, one can observe athletes at the international level who possess significant development of the muscles of the upper extremities, even at the present time in the modern biathlon era. These athletes typically have difficulty in the jerk. The difficulty is most apparent when the jerk is preceded by a difficult, but not an excessively difficult clean. On the other hand, one can observe lifters at all levels successfully jerk a heavy weight despite a very difficult clean; these lifters typically are not overly developed in the upper extremities.

An example is Jeff Michaels who was the top American heavyweight of the early 1980s. He had a best result in the clean and jerk of 220 kg and a jerk from stands of 240 kg. Yet, he had difficulty military pressing, at best, 100 kg. Furthermore, Michaels often experienced considerable difficulty rising from the deep squat position of the clean. Despite his apparently “weak upper extremities” and the strain of a hard recovery from the deep squat position, Michaels rarely missed a jerk.

How is it a high – class lifter will miss jerks despite devoting time to pressing exercises in training for the jerk and at the same time perform a less exhausting recovery from the deep squat than a lifter like Michaels? Many of these athletes apparently possess greater strength in the upper extremities because they have larger muscle mass in the arms and shoulders and are better conditioned (Michaels only trained once a day, 4 to 5 days per week). Logic then dictates that the “weaker” athlete over – all, who has strained more in the clean, would be the one most likely to fail frequently in the jerk.

Consider this possible explanation. The fundamental strength to lift the barbell in the jerk is the so called “reactive strength” of the legs. This specific strength/skill involves rapidly “braking” the downward movement barbell in the half squat and then instantaneous switching from bending to straightening the legs. The aforementioned action is followed by an explosive rearranging of the feet in the split position

The effectiveness of the jerk depends a great deal on the speed of switching directions from squatting to jerking, to splitting under the barbell (7,19,24,36,38,39,40,41,43,46,48). This action has to be performed in a fraction of a second. A weightlifter has to rely on a well developed motor habit to do this. This precludes any possibility the weightlifter can consciously “think” his way through this action.

A “weak” lifter like Michaels with his modern “pear” shaped physique developed and strengthened the motor habit to perform the jerk with only one strength i.e., the “reactive strength” of the lower extremities or what has been referred to as “the mechanism” (41). Although the high ranking lifter with the big muscles in the upper extremities possesses the same “reactive strength,” he may form a different motor habit when it comes to jerking a barbell. This athlete may have a motor habit which involves the complex coordination of “two strengths” in the jerk, i.e., the “reactive strength” of the lower extremities and the pressing strength of the upper extremities. The very same athlete (with the developed upper extremities) is able to overcome near – maximum weights after a not too taxing clean with the motor habit of “two strengths.”

However, a difficult clean typically “discombobulates” the stronger athlete (who has “two strengths”) such that he is unable to manage a precisely coordinated, sequential use of the legs and the arms in the jerk. On the other hand, a significantly harder clean executed by someone like the “weaker” and “pear shaped” Michaels does not have an appreciable affect on his jerking ability.

According to Frolov (41), the athletes who have high results in the jerk “rapidly execute the braking phase (from 0.10 to 0.13 sec) and instantaneously switch to the ‘thrust’ even after a difficult recovery from the clean.” The difficult recovery does not adversely affect the lifter’s ability to deploy the “reactive strength” of the legs. Apparently, the strength of the legs which the lifter employs to recover from the clean is not connected with the “reactive strength” of the same muscles which are called upon in the “presence of fatigue” to lift the barbell overhead in the jerk, i.e., they are separate mechanisms.

On the other hand, the difficult clean may create a situation which leaves the “stronger lifter” confused as to how to best deploy the available “strengths” to lift the barbell in the jerk. In this instance the “stronger” athlete experiences difficulties in the jerk similar to the strong pressers of the triathlon era of weightlifting and a powerlifter who switches to weightlifting; the pressing strength of the upper extremities simply gets in the way. A “too early” use of the pressing muscles comes at the expense of the full use of the muscles of the lower extremities which are the muscle groups best suited to execute this task.

The Connection Between the Special Strength for the Jerk and the Acquisition of Skills: “The 600 Pound Clean and Jerk”

“Success in the selection of the means of special strength training is determined by knowledge of the biomechanics of the movement” (27).

The formation and perfection of the weightlifter’s jerk technique is closely connected to the training methodology. Since the jerk is not a separate exercise but the second half of the clean and jerk, the technique of this part is an inter conditionality of the first part of the exercise, the clean. In acquiring the skill to perform this exercise, the lifter needs to possess isometric strength in the back muscles, absolute, explosive and reactive strength in the legs, absolute and isometric strength in the arms and shoulders, i.e., the strength for the clean and jerk is a “composite of special strengths.”

That being said, it seems logical that the basic training methodology for the clean and jerk would be to acquire these “special strengths” through the correct selection of exercises and training weights designed to produce the desired results. Over the years numerous exercises have been employed by weightlifters as assistance exercises for the jerk. However, the selection of these exercises in some cases has been misguided.

According to Y.V. Verkhoshansky (27) “the necessity of selecting the training means (particularly for the development of strength) based on the motor specifics of a concrete athletic exercise is one of the most valuable methodological ideas in sport.” In simple terms, one needs to select the assistance exercises for an exercise like the jerk based on the specific requirements of a successful jerk with a limit or near limit weight.

An article published in a popular bodybuilding magazine in 1967 is of interest with regards to how a practical selection of training exercises might go awry because of an unscientific analysis of the biomechanics specifics of the clean and jerk. The author of “Speculations on the 1st 600 Pound Clean and Jerk” (49) predicted that a 600 pound lift would be possible. He described the type of athlete who could achieve it and the composition of the specific “strengths” needed to achieve it.

The author was quite knowledgeable about the sport of weightlifting. For instance, he predicted accurately in 1967 that a 500 pound clean and jerk would be achieved in 1970; and, his prediction that 600 would be reached in 1990 was not – too – far – fetched. This feat would very probably have been accomplished were it not for the advent of out of competition drug testing.

In this article, the author described the clean and jerk as “a very high dead lift”, a vigorous front squat usually from a dead stop position, and a vicious quarter squat to fling the bar overhead” (49). Subsequently, the author “translated” the just described three phases of the lift into the requirements for a 600 pound clean and jerk as “1) the ability to dead lift 850+ pounds so that 600 pounds can be pulled briskly; 2) the ability to squat with 900 pounds, or front squat with 700 pounds, so that a recovery from a 600 pound clean is not too taxing; 3) the ability to do partial squats with 1500 and more, so 1000 feels like a toy and 600 can easily be jolted up.” He further states that “the 600 pound jerker will have to prone (bench press) 575 to 625 pounds and do overhead supports with 800 to 1000 pounds” (49).

The purpose of citing these figures is not to hold anyone up to ridicule, but to examine the source, i.e., the reasoning behind this “composite of strength” concept. Although this article was published almost 40 – years ago, we are of the opinion that this reasoning persists in the minds of many to the present day.

Let’s consider objectively, for a moment, each of the “necessary abilities” a weightlifter would need to clean and jerk 600 pounds. First, the clean is not a fast dead – lift followed by a drop under the barbell. The absolute strength required of a 850+ dead – lift involves a relatively slow speed muscular contraction. The coordination structure is not at all similar to the rapid switching of tension/relaxation of the antagonists of the lower extremities which occurs in the pull phase of a clean. So, this exercise and this amount of weight will have little carry over value, if any, to the clean.

A 900 pound squat would represent a ratio of 66% clean and jerk to squat. This is overkill to say the least. The loading of the spine to achieve this result is unjustified (27). A technically proficient clean is a skill. The technically proficient athlete of today skillfully utilizes the reactive forces of the muscles and the elasticity of the bar to recover economically from the squat position. Training for conditions of a dead stop at the bottom of the clean is to neglect the skill and concentrate on brute strength.

It is known that a weightlifter generates more force in the half squat for the jerk than is possible even under isometric conditions at the same knee and hip joint angles.(2,15, 36) Consequently, the force a weightlifter could generate performing 1500 pound quarter squats, which by its very nature is slow, is not at all comparable to how the force is produced in the technically efficient performance of the jerk. The force a top class lifter generates from a technically proficient half squat and thrust phases of the jerk not only exceeds that of a big quarter squat, but it is generated much faster and, therefore, is specific to the jerk.

A support reaction of 230 – 245% of the weight of the barbell in the jerk proper phase of the jerk is considered to be in the optimum range. When this force approaches “only” 200% of the weight of the barbell the weightlifter is advised that his speed – strength is lacking; he should then try exercises such as depth jumps to enhance his ability to quickly switch from bending to straightening the legs.

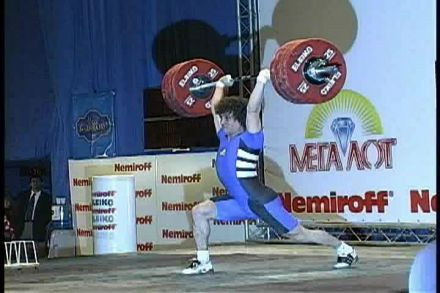

N. Pechalov (CRO) jerks 182.5 kg at 2004 European championships.

Those sections of this discourse which have dealt with pressing exercises and the strength of the upper extremities showed that the development of strength in the upper extremities to an “unnecessary level” may result in these muscle groups becoming more a hindrance than a help to the correct execution of the clean and the jerk. So, a bench press of 575 to 625 pounds and overhead supports with 800 to 1000 pounds are unnecessary and a waste of time and effort.

Curiously enough, a convincing argument against the development of unnecessary absolute strength is presented in the very same article. The author indicated that these “composite strengths” were not only achievable, but that 1956 Olympic Champion Paul Anderson (USA) had already done them. For instance, Anderson could squat 1100 to 1200 pounds, bench pressed 600, did partial squats with 2000 pounds, and even push pressed 560 pounds.

Despite this fantastic strength, the author concedes, Anderson was not even the first to clean 500 pounds. In fact, Anderson at a bodyweight of 160 kg had a best result of 200 kg in the clean and jerk which is only 3.5 kg in excess of the current world record in the men’s 69 kg class. Anderson’s bodyweight was more than double that of the 69 kg lifter who holds the world record in the clean and jerk.

Soviet weightlifting literature, extensive practical experience and anecdotal evidence indicate that it is unlikely a weightlifter can adequately prepare to increase results in the clean and jerk by developing a “composite” of strengths arbitrarily determined as the bio – mechanical requirements of the exercise. The strength needed for the jerk is best developed by monotonously perfecting the skill to perform the movement with maximum efficiently.

For example, the skill involved in displaying the “special strength” of the jerk is developed to the highest level by the lifters of the light weight classes. According to Roman (48), “Athletes in the light weight classes do not even lift the barbell to one half the necessary height for fixation (solely through acceleration),” i.e., the half squat and thrust phases of the jerk contribute less than half the force needed to lift the barbell to arms length.

It is known that in connection with the larger weights which are lifted today, the lighter lifters rearrange their feet in the split position at a relatively greater distance. Their trunks are lowered a distance of about 20% of their height as compared to an average of 15% for all weight classes. (48) However, this is not to be interpreted to mean that they merely “drop” lower under the barbell.

Relative to their bodyweight, the lightweights lift significantly heavier weights than the heavyweight lifters. However, the heavier athletes lift the barbell to a relatively greater height as a result of the half squat and thrust phases of the jerk. There are essentially two reasons for this. First, the weights lifted are smaller in comparison with the heavier lifters’ bodyweight. Second, the heavier lifter lifts bigger weights in absolute terms. The bar bends more with bigger weights; consequently, there is “less weight” to overcome because of the “extra lift” one gets from effectively utilizing the elastic deformation of the bar.

The lifters in the light weight classes who lift 275% to 300% of bodyweight in the jerk cannot benefit as much from the elasticity deformation of the bar in the jerk. Povetkin and Vilkovsky (54) concluded that the heavyweights obtained a disproportionate benefit from the affect of the weightlifter’s utilization of the elastic deformation of the bar in the press.

The authors believed that the greater bending of the bar in the press with the bigger weights lifted by the heavyweights was the principle reason the world records of the press and the clean and jerk converged in these weight classes at the end of the press era. For instance, in 1972 the following world records were in effect:

60 kg Class

Press: 137.5 kg – Foeldi HUN

C & J: 158 kg – Hsiao Ming Siang CHN

110 kg Class

Press: 213.5 kg – Kozin USSR

C & J: 222.5 kg – Talts USSR

110 kg +

Press: 236.5 kg – Alexeyev USSR

C & J: 238 kg – Alexeyev USSR

These records show that the Olympic press records were almost indistinguishable from the jerk for the heavyweights. Whereas, for all intent and purpose, the same technique employed by the lightweights was not as effective in “drawing” the results in the press close to the clean and jerk.

In order to lift up to more than 300% of bodyweight in the jerk, the lightweights compensate for the inability to produce sufficient acceleration from the half squat and recovery phases of the jerk by executing the “second jump” (the scissoring of the feet in the split) more forcefully than the heavier lifters. The second jump enables the lifter to impart sufficient acceleration to the barbell following the recovery from the half squat to lift it to arms length. The disproportionately greater distance the feet are placed apart in the split is indicative that this “second jump” of the lighter lifters is executed more energetically than the heavier lifters.

Consequently, the wider split position is indicative of the fact that the feet of the lighter lifters “were pushed off the platform more powerfully (than their heavier counterparts) and that there was a greater influence on the barbell during the squat under” (48).

The belief that one can improve the jerk through acquiring a “composite of absolute strengths” is an unsound attempt at a “metaphysical mechanization of weightlifting technique,” i.e., an unsubstantiated belief that the body is a machine and at the same time can function outside the laws of physics.

The jerk is in all probability the most powerful motion the human body performs in sport. The strength which is displayed in the jerk is a “reactive movement skill” and not simply an amalgamation of partial absolute strengths, as some would believe. Coaches and athletes alike have to exercise caution with regards to the selection of any assistance exercise ostensibly for the purpose to improve one’s results in the jerk.

References

1 From Sovietsky Sport Publishers, Publication #239:1988.

2 Vorobeyev, A.N., Tyazhelaya Atletika, Fizkultura i Sport, Publishers, Moscow 1972, pp: 63; 93 – 111. Translated by Andrew Charniga, Jr.

3 Frolov, V.I., “Analysis of Kinematic and Dynamic Parameters of the Movement of the Athlete and the Barbell”, Published by the Lenin State Central Institute of Physical Culture, 1980. Translated by Andrew Charniga, Jr.

4 Falameyev, A. I., Salnikov, V. A., Kimeishei, B.V., “Some Observations about Weightlifting Technique,” The P. F. Institute of Physical Culture, Lenningrad, 1980. Translated by Andrew Charniga, Jr.

5 Verkhoshansky, Y.V., Fundamentals of the Special Physical Preparation of Athletes, Fizkultura I Sport, Publishers, Moscow, 1988:17.

6 Charniga, A., “The Relative Value of Pulling Exercises in the Training of Weightlifters,” Sportivny Press, www.dynamic-eleiko.com 2003.

7 Sokolov, L.N., “Modern Training of Weighlifters”, Weightlifting Yearbook, 1974:4 – 8 Fizkultura I Sport, Publishers 1974, Translated by Bernd W. Scheithauer, M.D. 1975.

8 Luchkin, N.I., Tyazhelaya Atletika, Fizkultura I Sport, Publishers, Moscow, 1962, Translated by Andrew Charniga, Jr.

9 Quote attributed to Charlie Francis on the Internet, 2002.

10 Medvedyev, A.S., Tyazhelaya Atletika I Metodika Prepodavaniya, PP:25; 90. Translated by Andrew Charniga, Jr.

11 Frolov, V.I., Efimov, N.M., Vanagas, M.P.,“The Training Weights in the Snatch Pull,” Tyazhelaya Atletika, Fizkultura I Sport Publishers, Moscow, 1977: 65 – 67. Translated by Andrew Charniga, Jr.

12 Medvedyev, A.S., Melkonyan, A.A., Frolov, V.I., “Experimental and Theoretical Comparative Analysis of Clean and Snatch Technique”, Weightlifting Yearbook 1985, pp 85 – 89, English Translation, Sportivny Press, Livonia, Michigan. Translated by Andrew Charniga, Jr.

13 Matveyev, L.P., Fundamentals of Sport Training, Progress Publishers, Moscow 1981:25 – 26.

14 Engels, F., Dialectics of Nature, International Publishers, New York, 1973.

15 Vorobeyev, A.N., Tyazhelaya Atletika, Fizkultura I Sport, Publishers, Moscow, 1981.

16 Enoka, R. M., Neuromechanics of Human Movement, pp 353:2001, Human Kinetics, Publishers.

17 Astrand, P., Rodahl, K., Dahl, H. A., Stromme, S. B., Textbook of Work Physiology, Human Kinetics, Publishers, Champaign, IL 2003, p 328.

18 Kanyevsky, V.B., “Teaching the Starting Position of the Snatch and the Clean and Jerk to Novice Weightlifters,” Weightlifting Technique and Training, 1992, English Translation, Sportivny Press, Livonia, Michigan. , English Translation, Sportivny Press, Livonia, Michigan, Translated by Andrew Charniga, Jr.

19 Sokolov, L.N., “The Significance of Speed in Weightlifting and Methods to Develop It”, Tyazhelaya Atletika, Sbornik Statei. Fizkultura I Sport, Publishers, Moscow 1971:111 – 118. , English Translation, Sportivny Press, Livonia, Michigan. Translated by Andrew Charniga, Jr.

20 Vorobeyev, A.,N., Tyazhelaya Atletika, I Sport, Moscow, Publishers, 1977, pp 6 –7.

21 Chernyak, A.V., “ The Optimal Ratio of the Triathlon Exercises.” Tyazhelaya Atletika, Sbornik Statei. Fizkultura I Sport, Publishers, Moscow, 1971: 18 – 24. English Translation, Sportivny Press, Livonia, Michigan. Translated by Andrew Charniga, Jr.

22. Martyanov, S.S., Popov, G.I., Roman, R.A., “Peculiarities of Modern Clean Technique”, Weightlifting Training & Technique, English Translation, Sportivny Press, Livonia, Michigan. Translated by Andrew Charniga, Jr.

23 Samusevitch, A.K., Tyazhelaya Atletika, Belarus, Publishers, Minsk, 1967:88. Translated by Andrew Charniga, Jr.

21 Chernyak, A.V., “ The Optimal Ratio of the Triathlon Exercises.” Tyazhelaya Atletika, Sbornik Statei. Fizkultura I Sport, Publishers, Moscow, 1971: 18 – 24. English Translation, Sportivny Press, Livonia, Michigan. Translated by Andrew Charniga, Jr.

25 Abadjayev, I., “The Preparation of International Class Weightlifters,” Proceedings of the IWF Coaching Medical Seminar, Varna, 1983:57 – 63.

26 Frolov, V.I., “The Optimal Phasic Structure of the Snatch of Highly Qualified Weightlifters”, Tyazhelaya Atletika Ezhegodnik. 1977:52 – 55, Fizkultura I Sport Publishers, Moscow. Translated by Andrew Charniga, Jr.

27 Verkhoshansky, Y.V., “Fundamentals of Special Strength Training in Sport,” English Translation, Sportivny Press, Livonia, Michigan 1986:62 Translated by Andrew Charniga, Jr.

28 Charniga, A., “Key Muscles for Weightlifting,” Sportivny Press, www.dynamic-eleiko.com 2002.

29 Roman, R.A., Shakirzyanov, M.S., “Clean and Jerk Technique of Y. Vardanyan,” Weightlifting Yearbook 1980, English Translation, Sportivny Press, Livonia, Michigan 1986: 38 – 45, Translated by Andrew Charniga, Jr.

30 Roman, R.A., Shakirzyanov, M. S., “Clean and Jerk Technique of V. Marchuk,” Weightlifting Yearbook 1982, English Translation, Sportivny Press, Livonia, Michigan 1984: 31 – 3. Translated by Andrew Charniga, Jr.

31 Roman, R.A., “Snatch Technique of World Record Holder Y. Zakharevitch,” Weightlifting Yearbook 1983, English Translation, Sportivny Press, Livonia, Michigan 1984: 15 – 24. Translated by Andrew Charniga, Jr.

32 Roman, R.A., Shakirzyanov, M.S., “The Snatch of D. Rigert” The Snatch, The Clean and Jerk, Fizkultura I Sport, Moscow, 1978. English Translation, Sportivny Press, Livonia, Michigan. Translated by Andrew Charniga, Jr.

33 Covey, S. R., The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People, Fireside, Simon & Schuster New York, publishers, 1989, pp 95 – 144.

34 Dvorkin, L.S., Weightlifting and Age, English Translation Sportivny Press, Livonia, Michigan. Translated by Andrew Charniga, Jr.

35 Charniga, A., “Concerning the Russian Squat Routine,” Sportivny Press, www.dynamic-eleiko.com, 2002.

36 Sokolov, L.N., “Special Physical Training of Weightlifters,”Tyazheloatlet: V Pomosch Treneru, Fizkultura I Sport, Publishers, Moscow 1970, Compiler R.A. Roman, pp 78 – 87. Translated by Andrew Charniga, Jr.

37 Shakirzyanov, M.S., “Technique Peculiarities of World Champion David Rigert,” Weightlifting Yearbook 1974, English translation Bernd W. Scheithauer, M.D.

38 Ivanov, A.T., Roman, R.A., “Components of the Jerk from the Chest”, Tyazhelaya Atletika 1975: 23 – 26. Translated by Andrew Charniga, Jr.

39 Ivanov, A. T., Roman, R.A. “The Jerk Technique of World Record Holders V. Kurentsov and D. Rigert” Tyazhelaya Atletika, 1976:42 – 47. Translated by Andrew Charniga, Jr.

40 Ivanov, A. T., Roman, R.A., “Peculiarities of Jerk Technique of Weightlifters” Weightlifting Yearbook 1981. pp 43 – 54, English Translation, Sportivny Press, Livonia, Michigan. Translated by Andrew Charniga, Jr.

41 Frolov, V.I., Levshunov, N.P., “The Phasic Structure of the Jerk,” Tyazhelaya Atletika, 1979. pp 25 – 28. Translated by Andrew Charniga, Jr.

42 Furnadzhiev, V., Abadjayev, I., “The Preparation of the Bulgarian Weightlifters for the 1980 Olympics”, Weightlifting Yearbook, 1980, English Translation, Sportivny Press, Livonia, Michigan. Translated by Andrew Charniga, Jr.

43 Medvedyev,A.S., Masalgin,N.A., and Frolov, V.I., Herrera, A.G., “The Interconnection Between the Parameters of the Jerk,” Teoriya I Praktika Fizicheskoi Kultury, 6:6-7:1981. Translated by Andrew Charniga, Jr.

44 Sokolov, L.N., “Some Questions About the Technique and Methods of Training the Clean and Jerk,” Tribuna Masterov, 1963, Moscow :81-90. Translated by Andrew Charniga, Jr.

45 Sorokin, M., “Some Questions about the Training of Weightlifters”, Tribuna Masterov, Moscow, 1963:133

46 Abadjayev, I.N. and Furnadzhiyev, V.L., Podgotovka Na

Tezhkoatleta, Meditsina I Fizkultura, Sofia, 1986, pp 95.

47 Alabina, V.G. and Krivnosova, M.P., Trenazhery I Spetsialny Uprazhneniya v Legkoi Atletike, Fizkultury I Sport, Publishers, Moscow 1982.

48 Roman, R.A., The Training of the Weightlifter, Fizkultura I Sport, Moscow, 1986. English Translation Sportivny Press, Livonia, Michigan. Translated by Andrew Charniga, Jr.

49 Weider, J. “Speculations on the First 600 Pound Clean and Jerk,” Muscle Bulider, 9:6:40-41, pp 63-64: 1967.

50 Boevski, G., Personal Communication.

51 Verkhoshansky,Y.V. Programming and Organization of Training, English Translation, Sportivny Press, Livonia, Michigan, 1988:3. Translated by Andrew Charniga, Jr.

52 Sokolov, L. N., “Reasons for the Lagging of the Snatch,” Teoriya I Praktika Fizicheskoi Kultury, 1965:10:41, pp. 43–45 Translated by Andrew Charniga, Jr.

53 Kozlovsky, Y.I. Speed Strength Training of Middle Distance Runners, Zdovovya, Kiev, 1980: 16 – 17.

54 Povetkin, Y.S. and Vilkovsky, Y.V., “Biostructure of the Modern Press,” Teoriya I Praktika Fizicheskoi Kultury, 1972:6:11- 12. Translated by Andrew Charniga, Jr.

55 Sokolov, L.N., “The Rhythm of Movement of the Weightlifting Triathlon Exercises,” Teoriya I Praktika Fizicheskoi Kultury, 1960: 575 – 580. Translated by Andrew Charniga, Jr.

56 Laputin, N.P. and Oleshko, V.G., Managing the Training of Weightlifters, English Translation, Sportivny Press, Livonia, Michigan 1988:3. Translated by Andrew Charniga, Jr.

57 Khairullin, R., “Stabilizing the Technique of the Jerk,” Olymp Magazine 2:16 – 17:2002. Translated by Andrew Charniga, Jr.

58 Abramovsky, I., “A Weightlifter’s Excess Bodyweight and Sport Results”, Olymp Magazine 1:28 – 29:2002. Translated by Andrew Charniga, Jr.

59 Rodionov, V.I. , “The Press,” Tribuna Masterov :24 – 41:1963. Translated by Andrew Charniga, Jr.

60 Sokolov, L.N., “The Clean and Jerk Technique of V. Alexeyev” Tiazhelaia Atletika: 39 – 41: 1976. Translated by Andrew Charniga, Jr.