Reverse Engineering Injury Mechanism:

Achilles Tendon Ruptures and the NFL

Andrew Charniga

SportivnyPress.com

2016

“The speed at which animals can turn depends on the forces involved in cornering, and larger animals need to produce greater forces for any given turn. However, larger animals can apply relatively less force than smaller animals for turns and so cannot turn as rapidly.” R.Wilson, I. et al 2015

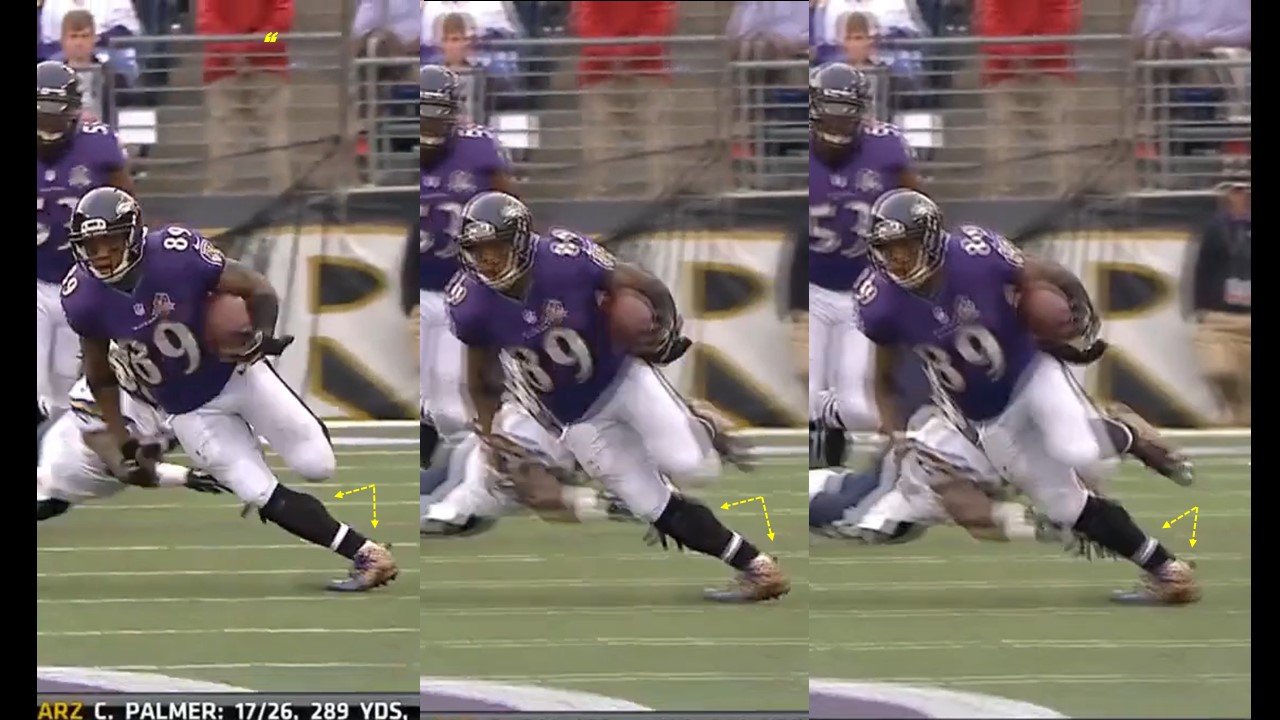

Figure 1. Professional football player ruptures Achilles tendon cutting to avoid tackle in open field. In general, strength and conditioning exercises and techniques employed for football players fail to take into account actual game conditions: to pursue and avoid pursuit. Sharp changes of direction necessitate lowering body center of mass and subjecting the lower extremities to increased loading to produce the centripetal acceleration for tilting the body and at the same time prevent toppling over (Biewener, 2007; Wilson, 2015). The viscoelastic properties of the tendons, especially the Achilles, come into play to enhance the body’s ability to produce those forces to make sharp turns without toppling over.

Three essays (“Its all connected” parts I-III) dealt with various issues relating to ubiquitous misinformation inspired by the academic and medical communities, research flawed by gender bias and the possibility to employ a ‘reverse engineering’ concept to gain insight into injury mechanisms in sports, were elucidated.

In an effort to gain objective insights into some common sports injuries to the lower extremities; the low injury rate of weightlifters principally to the ankle joint, and, especially among females were examined. Most of the examples presented were of female weightlifters, who would be expected according to the biased thinking of American academia, to suffer certain injury.

The non – injury events were explained within the context of special reactive physical qualities acquired through training for Olympic style weightlifting competitions. It was reasoned these reactive physical qualities are injury prophylactic.

A general conclusion formed from these essays was the all the too apparent lacking of these qualities in the preparation of many American athletes; hence the high injury rate of ankles and knees. To continue along the same line of reasoning of reverse engineering mechanisms; this essay will focus on one injury in particular, a rupture of the Achilles tendon in professional American football.

Is there a connection between predisposition for injury and exercise techniques?

The answer to the question as to whether certain exercise techniques, specifically, strength and conditioning exercise techniques popular in the training of football players from high school to professional ranks can predispose one to injury is an unequivocal yes.

How To Go About Breaking Biological Springs

“We run and jump in a similar fashion, stretching our Achilles tendons by about 5% as we stress them with forces around seven times our weight. We also store energy in the tendons of our feet themselves.” Steven Vogel, 1988

It should be emphasized such a simple assertion that strength and conditioning exercise techniques can predispose one to injury; must be inclusive the influences of the medical community, the academic community, the athletic training and physical therapy professions exert in the training room and on the athletic field. For example, a by no means comprehensive list of sources which influence conditioning techniques and methods is presented below.

- Bodybuilding; Powerlifting

- The National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA)

- Equipment manufacturers

- Personal training associations

- Strongman competitions

- Exercise emporiums

- Professional athletic trainers

- Physical therapists and orthopaedic surgeons

- Questionable research: especially gender biased

- University sports medicine programs and textbooks

- Olympic lifting

- Online gurus

Indeed, the influence of the various sources are obvious from the amalgamation of strength and conditioning exercises and techniques to be found in school, university and professional football weight rooms; and, are part of the training in certification programs:

- Exercise techniques, especially strength training exercises, tend to be choreographed to conform to arbitrarily defined limitations of movement deemed ‘safe’;

- Exercise techniques can be based on rudimentary knowledge of biomechanics and/or kinesiology;

- The ubiquitous presence of equipment manufacturers dictates most of the types exercises and the equipment used: racks; chains; benches; machines; bands; ropes; tires; balls, etc.;

- The teaching and mastery of complex motor skills in general, are antithetical to exercises employed in weight rooms;

- Exercise to fatigue and/or prolonged straining over single repetition in weightlifting exercises are frequently emphasized in strength training workouts for athletes.

A connection between the rather high number of Achilles ruptures suffered by NFL players, 13 for instance, by the first week of the 2011 season, and a single predisposing factor is not possible. However, such a connection is possible with the amalgamation of all the above influences, acting together over time. This conclusion is based on analysis of non – contact Achilles ruptures where there is no obvious predisposing factor such as another player or players falling on the injured or otherwise subjecting the tendon to unusual strain.

According to various sources in the literature (Khalid, Hsu, Shaginaw, Myer, Siebert) the frequency of Achilles tendon ruptures in the NFL appears to be on the rise; even though accurate data as to the precise number of incidents is hard to come by. The NFL is a business, not an open book; even though the overall injury rate is high; likewise the cost in human and financial terms.

Various misinformation can be ascertained relative to the etiology of such a devastating injury. From the little data available, approximately one third of football players are unable to return to the game after suffering an Achilles rupture. Many more have difficulty or are unable to return to their pre – injury power capabilities.

The generally acknowledged prevalence of at least 5 – 10 ruptures per year probably costs the league in the tens of millions of dollars. Surgery is usually necessary, recovery can take up to a year; replacements have to be found while the athlete is recovering or if the injury is career ending.

Viewpoints vary as to how football players go about breaking the body’s largest, strongest spring, but not widely so.

From the standpoint of the orthopaedic surgeon, the mechanism of Achilles tendon rupture involves:

“Mechanisms leading to tendon failure involve the rapid loading of an already tensed tendon. Proposed mechanisms of loading or overloading that result in an Achilles tendon failure include a dorsiflexion force to the ankle with a strong contraction of the triceps surae muscle, pushing off of the weight-bearing foot with the knee in extension, and a strong dorsiflexion force on the plantar flexed ankle”. (Khalid, 2016)

This mechanism echos a viewpoint of the Achilles rupture etiology from athletic training:

“I saw a common mechanism for most of them. The athlete takes some kind of back step and as he pushes off, his knee extends at the same time. This combination of eccentric loading of the Achilles followed by forceful plantar flexion and knee extension may overload the tendon causing rupture”. Justin Shaginaw, (2015)

And, from another surgeon:

“Stepping backward onto the toes in order to push off the ground to suddenly start forward.”

“Pushing forward into opposing players by standing on the toes and driving the heel to the ground.”

“Stopping suddenly on the toes in an attempt to quickly change directions.” Seibert, (2011)

What this technical gobbledigook means is the body’s largest, strongest spring blows apart as a result of everyday, normal running, turning, jumping mechanics: extending the leg against a raised heel. How one can run about a football field, run and jump about a basketball court and so forth, without straightening the knee, hip and ankle without raising the heel, i.e., sans this biomechanics, is left to the imagination. Even more to the point, how can any explosive motion from the lower extremities be effective without all the muscles, tendons and ligaments working together in the just describe gobbledigook manner?

Consider the contrasting circumstances depicted in the three photos of figure 2. A 75 kg young woman is jerking a 154 kg barbell (205% of her bodyweight). The Achilles tendon of the football player’s right ankle ruptures at approximately the instant he pushes off while running with the ball.

The difference between the massive strain (normal for weightlifters) on the lifter’s tendons and that of the football player’s Achilles, who suffered a serious injury is the woman’s ‘spring’ stretches, elongating up to 5 – 6% of its length to store strain energy. On the contrary, the football player’s tendon ruptures as it resists by comparison a modest, natural elongation. There is nothing out of the ordinary or unusual about the conditions under which the football injury occurred.

Tendons are designed to store and release elastic energy, that is why they are referred to as viscoelastic. The weightlifter in the example dissipates the combined forces of the her bodyweight and the barbell on her tendons while storing strain energy. The elastic (strain) energy from the stretch is released just as a spring recoils, when the lifter pushes off to straighten her legs. More power is generated with this recoil than is possible from mere muscular contraction.

There is no logical argument, no amount of technical jargon which can demonstrate the relatively low stress tendon blow out circumstances of the football player are at all comparable to those of the everyday, massive strains on the weightlifter’s tendons. The young woman’s Achilles tendon and indeed the ankle joint, are subjected to strain far exceeding the rather modest forces on the tendons of the football player’s ankle; which resulted in serious injury.

“Whenever the Achilles lengthens too much too sharply, it can rupture.” (Seibert, 2011)

Were there any truth to the above statement Achilles tendon ruptures would abound; especially in weightlifting.

Figure 2. Female still in mid – air before landing back – foot – first to fix 154 kg barbell, with extremely flexed ankle. Compare this to football player at the approximate instant of rupturing Achilles tendon after planting foot while carrying a 450 gram football.

Figure 3. Female weightlifter lifting 154 kg, pushing off the rear foot from a extreme stretch of Achilles and other tendons and ligaments of the ankle and foot. Charniga photos

Another line of thinking about tendon rupture etiology is from the standpoint of conditioning coaches. Since a lot of these injuries occur in preseason or training camps it was reasoned (and this is echoed by the surgeons) the players were out of shape when they reported to camp and may have “Exercise deficit disorder”; a term used to describe young athletes: “who do not have enhanced physical prowess and necessary neuro – muscular control are at increased risk of injury, as evidenced by epidemiological reports on anterior cruciate ligament injuries….” Myer et al, 2011

Consequently, the authors concluded the rash of injuries which occurred in the immediate aftermath of the 2011 NFL lockout were due to the players reporting to training camp in the absence of sufficient time training with the strength and conditioning coaches, athletic trainers and medical staff ‘to ease them into the rigors of preparing for the football season’. (Myer et al, 2011)

Prematurely aging the younger athlete

In their review Myer, et all, 2011, noted that research of NFL Achilles ruptures established an average age of 29. Whereas, Myer, et al, found that of the rash of rupture injuries in 2011 the average age was 23.9 years. As already noted the authors attributed this catastrophic injury to a lack of time with the amalgamation of conditioning coaches, trainers and physical therapists; creating a sort of “Exercise deficit disorder”.

A far more plausible explanation for the rejuvenation of rupture victims is the cumulative effects from an earlier onset of bodybuilding/powerlifting exercises and techniques in strength training, ankle taping, i.e., restrictive range of motion exercises and supported taping, already, in high school. Surgeons typically see this type of injury with “40 – 60 year old” male weekend warriors playing pick up basketball and such (Stone, K., 2015).

The common thread between the NFL and the middle age rupture victims, unequivocally, is a loss of muscle – tendon elasticity. The football players have been ‘stiffened’ with bodybuilding/powerlifting exercises and a general lack of bending the hip, knee, and, especially the ankle through a large amplitude of motion; roughly equivalent to what happens to the weekend warriors: aging and lack of conditioning.

Were the assessment of Myer, et al, at all plausible there would be sufficient evidence to demonstrate Achilles ruptures were a common injury in the more than 100 year history of American football. And, with advent of the strength and conditioning coach, athletic trainers taping ankles and knees, taping shoes to ankles, knee braces, and so forth; the rate of Achilles ruptures would naturally decline because the players with “Exercise deficit disorder” would have begun to disappear, i.e., the ankles of young athletes would be better ‘conditioned’ and protected with tape and braces.

On the contrary, sans data preceding the appearance of the weight coach and ankle taping practitioners; most observers acknowledge the rate is rising. Furthermore, since when did this disease known as “Exercise deficit disorder” make its appearance?

The high rate of injury to the lower extremities, especially Achilles ruptures, strongly suggests something is radically wrong with the training and general preparation of football players

A logical explanation, with an extraordinarily high probability, is the etiology of such an unusual, devastating injury to young elite athletes can be traced to heavy reliance on bodybuilding/powerlifting exercises and methods in the strength and conditioning of football players. These practices are all the more problematical because they are coupled with the mobility altering use of taping/bracing of joints. This type of strength training over time produces ‘linear robots’; capable of running linearly; which in actuality, contradicts the typical demands of the game.

Figure 4. “Supra – stretched’ Achilles and other tendons of a female weightlifter’s lower extremities; with mechanical energy exponentially exceeding modest tendon snapping forces encountered on the football field. Charniga photo.

“At first glance, tendon looks like a poor spring. We’ve been talking it about it here as an inextensible spring, and a spring must stretch to be of any use. In reality, though, tendon can be stretched, just not very much; it breaks when elongated beyond about 8 percent.” Steven Vogel, 1988

Based on this statement by highly acclaimed biologist Steven Vogel, tendons are biological springs, the function and purpose of which is to stretch and recoil. These biological springs allow animals and humans to generate forces to jump further and run faster than is possible from contraction of all the muscles involved in these actions.

A tendon can rupture when it is stretched up to 8% of its length. That being the case, it is highly unlikely the rupture injuries common to the NFL involve stretching the body’s main springs to 8%. Why? Because very, very few if any of the players ever elongate their Achilles in weight room exercises or on the field remotely close to that of the young female weightlifters in the illustrations.

Consequently, after many years of powerlifting/bodybuilding weight room exercises, taping and spatting ankles, knees and so forth and normal playing conditions where the knee and ankles do not bend through a large amplitude of motion; the average NFL player’s range of motion, and especially the muscle – tendon elasticity of the lower extremities deteriorates.

In all probability the tendon ruptures because this loss of elasticity creates internal resistance to what should be normal coordination of muscles and elongation of tendons and ligaments from hip to foot.

The actions described above of football players extending lower extremities are normal movements and are precisely how humans and animals achieve power outputs unattainable by mere contraction of muscles.

Figure 5. Dialectical contradictions arise when serious non – contact football injuries to the lower extremities are contrasted with normal, non – injury inducing weightlifting exercises; this, despite significantly greater stress on the ‘un – protected’ lower extremities of weightlifters. Contrasting circumstances are depicted above of injury with normal versus high stress on lower extremities. From left to right: A serious knee injury occurs from non – contact running; a female executes a normal maximum bending in ankle joint while fixing 220% of bodyweight overhead in the clean and jerk; an Achilles tendon rupture from non – contact movement in football.

False notions of what constitutes acceptable movement amplitude in strength and conditioning exercises, taping, bracing and so forth, coalesce to ultimately to increase the vulnerability of the ankle joint tendons and ligaments in sports like American football

The idea that the ability to turn the ankle (inversion) rapidly could be part of a complex reaction; an injury prophylactic; does not exist in the world of athletic training

The ankle joint is full of Biological springs – called ligaments and tendons. That being said, it is illogical to arbitrarily determine ‘safe’ and ‘unsafe’ motions for the ankle; and of course it goes without saying; to likewise go about taping or otherwise restricting motion in joints which are set up to move in harmony, interconnected and inter-conditionally to all other joints.

See illustrations in figures 6-8:

Figure 6. Note: Perceived extremely narrow ‘safe’ range of movement of the ankle joint illustrated in the picture on the left and the obvious solution to ‘protect’ the ankle by ‘spatting’ the foot and ankle joint to the shoe.

“A human or animal body is a complex structure whose parts move relative to each other.” R. McN. Alexadner, 1988

Figure 7. Three photos depict female and male weightlifters twisting ankles. In each case the athlete twisted the ankle holding a heavy barbell overhead, without consequence. Charniga photos.

Figure 8. The single worst idea ever conceived in the realm of athletic training: ‘tighter ligaments’ , and the disastrous aftermath it has spawned. Football linemen wearing knee braces with high top shoes and no doubt, ankles taped for additional support to prevent injury. A stark contrast between football linemen required to “tighten” joints with braces with female weightlifter subjecting the lower extremities to extreme loading snatching 103 kg; sans any support other than bone, muscles, tendons and ligaments. Charniga photo on right.

Bodybuilding/powerlifting movements constitute the majority of exercises and techniques to be found in the high school, college and professional weight rooms. In general these exercises are not performed with full range of motion in joints; are performed slowly with heavy weights and/or become slow in one set with multiple repetitions. These exercises are low skill movements, relatively simple in motor structure; or, in the case of weight machines, movement constitutes antithetical skill. Furthermore, with heavy weights or prolonged contractions through multiple repetitions this type of training is almost indistinguishable from isometrics.

Strength training in this manner over a long period of time has been shown to reduce muscle – tendon elasticity. Hence, Russian sport scientists who studied the negative effect of bodybuilding/powerlifting exercises for strength training athletes in dynamic sports note:

“All of this has a negative effect on muscle elasticity, on their ability to stretch and relax, and an unfavorable effect on those sport exercises which require speed strength and precise movement coordination.”A.I. Falameyev, 1985

Figure 9. Elite collegiate football player suffers season ending knee injury attempting to decelerate; his right leg is injured with heel strike first, in pursuit of opposing runner who is cutting to avoid tackle.

More than sufficient evidence of the myriad influences affecting the training of football players from the list provided can be found in numerous weight room videos posted by universities and professional teams.

For instance:

/ www.youtube.com/watch?v=e-jopcihzmm

In this video the athlete is ‘coached’ to perform slow grinding half squats chained to a resistance machine;

/ www.youtube.com/watch?v=3zzVLRARNMo

In this video athletes perform powerlifting type squats with heavy weights, inside rack with depth of bending controlled, employ machines etc.;

/ www.youtube.com/watch?v=vtxsW8yydac

The coach in this video instructs athletes to squat, pointing out that he has good ankle flexibility. A classic example of the blind leading the blind, he sits back in half squat with shins vertical.

/ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xWBSf4BfKRk ACL injury prevention video demonstrates techniques to prevent knee injury. The concepts presented to bend a certain way with feet aligned with shin and so forth contradict the un-choreographed demands placed on the athletes’ lower extremities on the field.

/ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x7Bl7rMGQxc This video is a vivid example of the utter lack of any conceptual understanding of flexibility, suppleness, muscle tendon elasticity and so forth. How else can this be described other than a ‘carnival barker’ leading players ‘stretching’ boards at a lumber yard.

Compounding the “stiffening” effect of bodybuilding/powerlifting training in the football weight room; add the athletic trainer taping ankles, knees, shoes to ankles and so forth and over time, ‘linear robots’ emerge.

Consequently, it is precisely when the players report to training camp that these muscle – tendon – joint stiffening influences coalesce. When players’ whose muscles have been ‘stiffened’ by bodybuilding/powerlifting movements and machine exercises, take the field and are expected to perform dynamic, explosive movements with taping and bracing they are confronted with what the Russian sport scientists call ‘internal resistance’.

The agonists/antagonists involved in a motor action have to ‘cooperate’ in order to minimize internal resistance to movement and maximize power output. Furthermore, this ‘cooperation’ allows athletes to react to unanticipated conditions and avoid injury.

Consider the quote below referring to this concept of lessening internal resistance by training with movements of large amplitude.

“It is easy to stretch the muscle antagonists and thereby lessen the resistance to the power of the muscle agonists, the contraction of which perform the movement, if one possesses large movement amplitude.” A.N. Vorobeyev, 1988

It is rare if any football player exercises the knee, hip and ankle through a large range of movement. This, out of fear of bending the knee and ankle so far as to stretch ligaments and tendons, i.e., the influence of strength and conditioning coaches, trainers, academics, medical staff, etc. Consequently, the axiom from Biology ‘use it or lose it’, applies to the prospect of losing range of motion in joints and especially muscle tendon elasticity; after years joint stiffening exercises, taping and bracing of joints.

Conclusions

Weightlifters subject the lower extremities, especially the ankle joint and Achilles tendon, to forces far exceeding those of football players at any level; yet experience exceptionally low rates of injury to ankle and almost non – existent to Achilles tendon. Weightlifters train such that all the muscles, tendons and ligaments of the lower extremities perform as a single leg spring. The unrestricted movement of all the supple weightlifter’s joints, muscles, tendons and ligaments of the leg spring are interconnected, interdependent and of course, inter-conditional.

Figures 10-12. A contact ‘non – injury’ in weightlifting. Weightlifter drops 178 kg on his shank without suffering injury despite absorbing the full weight of the barbell. The elasticity of the lifter’s muscles and especially the Achilles tendon dissipate the energy of the falling mass which under analogous conditions one would expect something like this to lay waste to a whole football team.

The same cannot be said of the football players’ lower extremities; the elasticity of their muscles, tendons and ligaments can be compromised over time by bodybuilding/powerlifting, ie., slow exercises lacking full range of motion. Furthermore, the elastic mobility of the leg spring can be the compromised by artificially compartmentalizing the interconnected links, i.e., restricting movement of joints; with tape and supports.

There is sufficient anecdotal evidence that the strength training regimens of football players is made up of a preponderance of bodybuilding/powerlifting exercises and techniques. Over the long term of more than eight years, from high school to professional ranks, this has to adversely affect muscle tendon elasticity. This in turn, makes these athletes more susceptible to what should be an extremely rare affliction like an Achilles rupture; relatively common by the time a chosen few are able to play in the NFL.

Ankle injuries in weightlifting are extremely rare; but, rarer still are Achilles rupture. Conversely, not only are ankle injuries the most prevalent problem in football (especially non – contact injuries); but even no – contact ruptures of the Achilles tendon which should be extremely rare; are relatively common. The principle difference between the training of weightlifter and that of the football player is the weightlifting exercises demand and contribute to suppleness. The weightlifter’s lower extremities are subjected to a large amplitude of un -choreographed movement, without taping or braces to support and otherwise restrict motion. And, there in all likelihood lies the solution.

References

/ Charniga, A. “ It is all connected Parts I-III, www.sportivnypress.com

/ Charniga, A. “The foot, the ankle joint and an Asian pull”, Scientific Magazine, 5: 14-23:2016 http://www.ewfed.com/documents/EWF_Scientific_Magazine/EWF_Scientific_Magazine_EWF_N5.pdf

/Khalid, S. et al, “Return to football after Achilles tendon rupture”, http://lermagazine.com/article/return-to-football-after-achilles-tendon-rupture

/ Hsu, A., “Foot and Ankle Injuries in American Football” Am J Orthop: 2016:09:45(60:358-367)

/ Myer, G. et al, “Did the NFL lockout expose the Achilles heel of competitive sports”, J Orthop Sports Phys Ther, 2011:41(10);702-705; doi:10.2519/jospt.2011.010

/ Siebert, D., “Achilles Tendon Tears Plaguing NFL Teams After Week 1”, http://bleacherreport.com/articles/2192017-achilles-tendon-tears-plaguing-nfl-teams-after-week-1

/ Shaginaw, J., “Achilles Injuries on the Rise in the NFL?”, http://www.philly.com/philly/blogs/sportsdoc/Achilles-Injuries-on-rise-in-NFL.html

/ Biewener, A., Animal Locomotion, Oxford University Press, 2007

/ Wilson, R. et al, “Mass enhances speed but diminishes turn capacity in terrestrial pursuit predators”, http://dx.doi.org/10.7554/eLife.06487; eLife 2015;4:e06487

/ Stone, K. R., “Achilles Tendon Ruptures: The Scourge Of The Mid-Life Male”, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/kevin-r-stone-md/achilles-tendon-ruptures-the-scourge-of-the-mid-life-male-athlete_b_7941602.html