Andrew Charniga

www.sportivnypress.com

Weightlifting Exercises Out of Sync: Part II

Andrew Charniga

www.sportivnypress.com

Weightlifting exercises which sound good on paper

“Sometimes a lot of time is wasted developing muscles whose role in the snatch and clean and jerk are very insignificant”. Igor Abramovski, Olimp, 01/19:2006

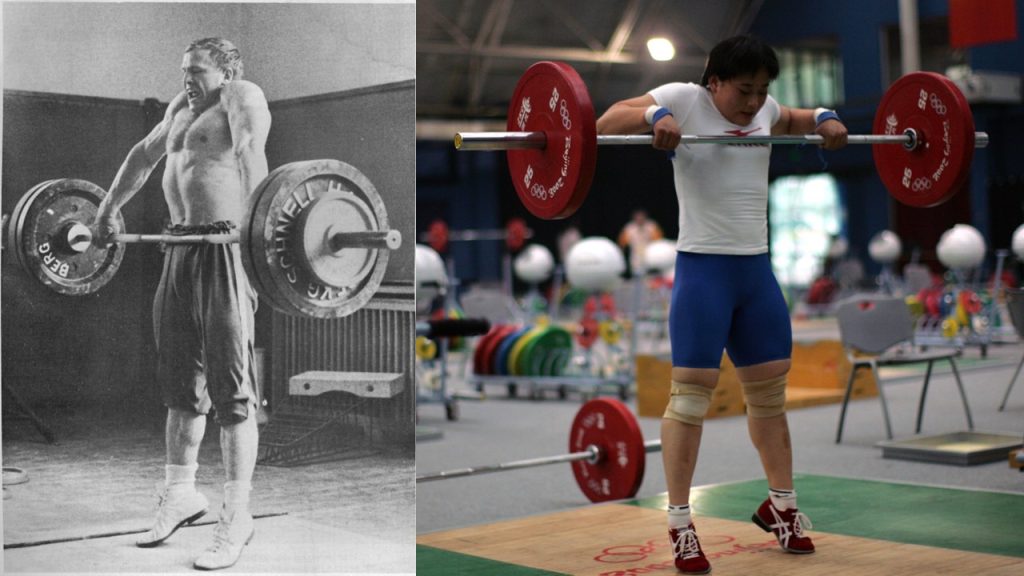

Figure A. Two depictions of what were and still are, erroneously considered ideal techniques to pull the barbell. On the left (Kono Photo) is a close to impossible exercise technique of straightening the trunk, knees, a complete rise onto the toes, maximum shoulder shrug – all the while with arms straight. On the right a similar full extension, heel raise shoulder shrug with fully flexed arms technique; in actuality, impractical for female lifters. Charniga photo

/ high pulls to a stick;

Considerable research led to consensus among various Soviet era weightlifting scientists to conclude technical proficiency in weightlifting is connected with a low maximum height of lifting the barbell in the snatch or the clean; coupled with a high speed of the descent under the barbell, i.e, both of which are interconnected and interdependent upon the speed of muscular relaxation. The inter-connectivity, the interdependence of those factors enable the elite weightlifter to successfully raise a slow moving barbell. The skill – set requisite to successfully lift a slow moving barbell is an indispensable attribute of the high class weightlifter.

The task of the classic exercises is to raise a maximum weight from the floor to fully outstretched of arms overhead (fixing at an approximate 180° angle of the elbow joint). The obvious circumstance must follow: the maximum height of lifting recedes as the weight increases. This in turn, forces the weightlifter to drop under the barbell as low as possible; since the maximum height regresses along with its increasing weight. Furthermore, a lifter must be able to drop down so rapidly as to exceed the acceleration of a free-falling body. Merely pulling the body down with arms and shoulders will not suffice. Consequently, a weightlifter has to develop the ability to relax muscles not just quickly; faster than he/she is able to contract muscles.

Figure 1. Depiction of what has been a popular special exercise for the snatch and to a lesser degree the clean. The aim is to raise the bar such that it will contact the stick lying across the stands. Photo on the far left depicts what is believed an optimum technique with trunk stretched to near vertical; whereas the next two depict what is considered poor technique as trunk leans backwards. Kono Photos.

Figure 1A. Contrast the relative disposition (height) of the barbell with lifters already flexing lower extremities to the dispositions of figure 1. The elite lifters in this figure are already descending and flexing legs at or below the height of barbell depicted in figure 1. The natural conditions of the classic exercises are completely different than the ‘sounds good on paper’ technique depicted in figure 1. Charniga photos

An assistance exercise for the snatch which has been popular in the past and is still used today is depicted in figure 1. Who came up with the idea for this exercise is debatable. It was featured in Strength and Health magazine in the early 1970s. However, weightlifting textbook (Gewichtheben) authored by East German weightlifting sport scientist Gerhard Carl featured this exercise. It is designed to develop pulling strength, such that the lifter learns to lift the weight to the right height to fix it. The German text featured both snatch and clean variants. The rigidity, the simplicity of the format of the exercise’s task; make it more likely it’s origins were European.

The basic premise of this exercise: one is to learn the necessary height of lifting in the pull to lift a maximum weight in the classic exercise. The height of lifting needed to fix a weight in either the snatch or the clean is determined for a given athlete. For instance, this was considered to be about sternum height for the snatch.

A wooden stick is fixed across two supports (see figure 1) at that predetermined height such that the end of the stick is fixed perpendicular to the end of the bar.

The athlete in the figure is attempting to raise the barbell in a snatch pull until the end of the bar contacts the stick laying across the stands. The stick is fixed at a height which conforms to the height of lifting, in theory, necessary to complete a classic snatch; relative to the given athlete’s height.

Consequently, the lifter practices that specific skill, i.e., the strength to pull the weight to at least that predetermined height. Presumably, by practicing this exercise; the lifter would learn to drop under the weight after the barbell has been raised to this height; when performing the classic snatch.

The three figures depict how the weightlifter should perform the exercise in order to practice lifting the bar to what is considered the correct height necessary to complete the snatch. In the photos depicted, from left to right, the lifter has fully straightened legs and trunk in endeavoring to hit the stick. The picture on the far left is considered the optimum technique as the lifter is relatively vertical, i.e., the bar has been raised higher because the lifter has ‘stood tall’. The next two pictures are used to illustrate as this ‘stand tall’ technique deteriorates, the barbell cannot be raised as high as in the first photo, i.e., the lifter is shorter as he strains to reach the stick with the bar.

The concept illustrated by the sequence of photos is consistent with the ideas of those days; which still persists. The belief persists weightlifters need to fully straighten lower extremities; raise the heels and shrug the shoulders, i.e., a ‘stand tall’ technique; to learn the correct method of lifting the barbell in the classic snatch.

Furthermore, a deviation from this ‘stand tall’ technique depicted in the sequences where the lifter has bowed (leaned backwards) the body to lift the barbell is considered inefficient. Bowing will not permit the lifter to raise the barbell high enough to touch the stick; and so the thinking goes.

Soviet era research of weightlifting biomechanics showed there are a number of flaws connected with the concept of a ‘stand tall’ then drop under technique as depicted in the sequence photos:

/ the minimum height of lifting in snatch; for instance, needed for a given athlete is not a fixed parameter based on his/her height (A. V. Chernyak, 1969).

/ lesser qualified lifters raise the barbell higher (relative to their height) in order to fix the weight in the low squat (A. V. Chernyak, 1969). .

/ elite lifters (especially world record holders in snatch) will ‘find’ the minimum height required to fix the barbell over time (A. V. Chernyak, 1969).

/ any effort to teach the changing parameters of height of lifting that accompanies the development of the weightlifter’s technical proficiency with a simplistic, arbitrarily determined fixed height to pull the barbell is highly unlikely to succeed.

/ regardless of how ‘tall the lifter stands’ in the pull exercise; even with heels raise and shoulder shrug; he/she will not be able to raise the barbell as high as is possible to lift the same 100% weight in the classic snatch (Chernyak, 1971).

/ a classic snatch with a 100% weight will raise the barbell higher than is possible in pulls with the same 100%; because the inertia of the athlete’s descent into the squat adds a lifting force on the barbell; which is absent in pulls;

/ a rearward bar trajectory, i.e, the 3rd curve in the movement of the barbell as it approaches its maximum height; is absent in the pull (see Charniga, “The secret to the weightlifter’s strength: speed of muscle relaxation”);

/ a timely squat under the barbell is unjustifiably delayed ‘waiting’ for the lower extremities and trunk to fully straighten;

/ forcefully straightening the knees past an angle of 165º requires extra work without imparting lifting force on the barbell. It is further counterproductive to raising the barbell by delaying the instantaneous switching to descending into the squat; a ‘pre – mature’ heel with the re-bending of the knees is more effective for producing a vertical force against the barbell;

Figure 2. Falsely assumed to be ‘pre – mature; a heel raise with knees still flexed; is more effective than fully straightening the knees in the pull as advocated to learn with the pull to the stick. Charniga photo.

/ a lifter should already be squatting down at the instant the barbell reaches its greatest height (I.P. Zhekov, 1976); which on is purportedly practicing with the pull to stick.

In point of fact, the weightlifter needs to be descending under the weight before the barbell reaches its maximum height of lifting in the classic snatch. In virtually all cases the barbell reaches maximum height at the instant the feet leave the platform as the lifter is already dropping into the squat (figure 2).

Figure 3. A lifter should already be descending before full extension as depicted in figure 1.; the inertia of which contributes to raising the barbell. Charniga photo.

So, all things being equal; the entire premise of the pull to a stick exercise is inconsistent with the correct mechanics of optimum snatch technique. A lifter will learn the pull phases of the classic snatch wrong; with a counterproductive ‘stand tall’ technique; from practice of this pull to the stick exercise; a negative transfer of habits.

There is irony in the basic premise of the pull to the stick exercise. The idea one will learn how to raise the barbell to a sufficient height in order to successfully lift it in the classic snatch through practice of the pull to the stick is incorrect. A lifter will be practicing to lift the barbell to a lower height than is possible; and, in point of fact, necessary to successfully complete the classic snatch.

References

/ Charniga, A., “The secret to the weightlifter’s strength: speed of muscle relaxation”. www.sportivnypress.com

/ Charniga, A., “Weightlifting exercises out of sync”,\ www.sportivnypress.com

/V.I. Bystrov, A. I. Falameyev,“The Dynamics of Weightlifters Achievements” Weightlifting: Sbornik Statei 24 – 31:1971 Lenningrad

/ Vorobeyev, A.N., Weightlifting, 1988. English translation Sportivnypress, Livonia, Michigan

/ Zhekov, I.P., Biomechanics of the weightlifting exercises, 1976. English translation Sportivnypress, Livonia, Michigan

/ Frolov, V.I., Lelikov, S.I., Levshunov, N.P., “Criteria of the Weightlifter’s Technical Mastery”.Teoriia I Praktika Fizicheskoi Kultury3:17 -19 1978. Translated by Andrew Charniga

/ Roman, R.A., “The effect of large loading in pulls and squats on the weightlifter’s sport results”, Tribuna Masterov, FIS, Moscow, 26-40:1969. Translated by Andrew Charniga.

/ Roman, R.A., “The Training of B. Selitsky for the XIX Olympic Games”, Weightlifting: Sbornik Statei; 58- 62:1970. Translated by Andrew Charniga

/ Roman, R.A., “The Training of the High Class Weightlifter”, Tiiazhelaya Atletika Sbornik Statei; FiS, Moscow; 43-58:1970 Translated by Andrew Charniga\

/Verkovsky, F., “The clean with a deep squat”, Tribuna Masterov, FIS, Moscow, 1963. Translated by Andrew Charniga.

5/ Sokolov, L.N, “The Significance of Speed in Weightlifting and Methods to Develop it”. www.sportivnypress.com

6/ Zatsiorsky, V. M., Science and Practice of Strength Training, Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL. 1995