Incidence of Valsalva Episodes and Competition Protocols in Weightlifting

Andrew Charniga

Sportivnypress.com

Essentially “any forced expiratory effort against a closed airway” (Yale, S. 2005) is referred to as a Valsalva maneuver. Named after the Italian physician Antonio Maria Valsalva (1666 – 1723) who originated this maneuver; the Valsalva is still used in clinical evaluations; to evaluate heart murmurs and to assess left sided heart failures (Yale, 2005); to name just a few.

Weightlifting exercises with maximum weights are performed against a backdrop of a dialectical contradiction. On the one hand breath holding is a natural reaction while straining to lift a maximum weight. However, breath holding while straining to lift a big weight comes with the risk of a Valsava episode; a possible cascading loss of motor control, dizziness and so forth.

A Valsalva episode can result in the athlete blacking out i.e., losing consciousness. The black out results from “the reduced cardiac output and cerebral blood – flow associated with the Valsalva maneuvere” ( Compton, D & Hill, et al, 1974).

On the other hand, breath holding with closed glottis stimulates a reflex which in turn facilitates muscular contraction (Zatsiorsky, 1995):

“If maximal force is exerted while inhaling, exhaling, or making an expiratory effort with the glottis .. closed (Valsalva maneuver) the amount of force developed increases from inspiration to expiration to Valsalva maneuver. The underlying mechanism for this phenomenon is a pneumo-muscular reflex, in which increased intra-lung pressure serves as a stimulus for the potentiation of muscular excitability.” Zatsiorsky, V. M., Science and Practice of Strength Training, Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL. 1995

However, the coincidental spike in blood pressure and drop in heart rate can result in a black out (Valsalva) episode of varying intensity.

Figure 1. Female lifter collapses head first into the platform after suffering Valsalva episode at 2010 Senior World Championships. Charniga photo.

In the absence of reliable figures, it is nonetheless a safe bet that at least one athlete suffers a Valsalva episode of varying severity at every weightlifting competition. In a major competition like the world championships with 200 – 400 athletes taking part, one can only guess; but, it would be reasonable to anticipate a minimum of 8 – 10 episodes. Since most Valsalva incidents involve relatively minor motor impairment and/or dizziness; the underlying potential for injury to the athlete does not spur serious scrutiny, i.e., no harm comes to the athlete so special precautions are deemed unnecessary.

The weightlifting exercises involve maximum strain which can last up to several seconds. Consequently, with so many athletes endeavoring to raise maximum weights overhead Valsalva episodes are an unavoidable, yet accepted risk for the weightlifter.

That being said, it must be pointed out that current competition protocols, progressive in time, but backwards in sophistication; are inadequate to address possible consequences of a serious Valsalva incident.

Valsalva episodes were a common occurrence in the press era of weightlifting. However, in the modern era the Soviet textbooks indicate:

“Athletes who fall or otherwise pass out on the platform during a jerk or a press in training, and sometimes in the front squat, in the majority of instances, is caused by constriction of the carotid arteries when the sportsman places the barbell above the clavicles.” Vorobeyev, A.N., 1988

Observations of numerous episodes shows this is not necessarily the case. Furthermore, many elite lifters in the press era began the exercise with the bar placed off the clavicles on the upper portion of the chest in order to begin with shoulder girdle muscles stretched.

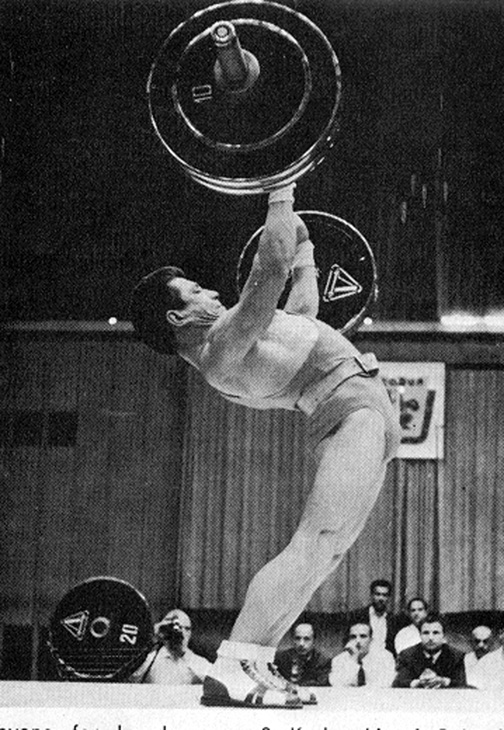

Pressing a maximum weight involves prolonged straining with a possible tilting the head back while straining to raise the weight. This was believed to exacerbate the possibility of a Valsalva episode. This connection could be observed in the 1950s when Soviet lifters began pressing with chin tilted down against the chest to prevent the head from leaning back. Tilting the head back while straining to press could make a Valslava episode more likely due to tightening of the anterior neck muscles; with the possibility of restricting blood flow in the carotid arteries.

Figure 2. Lifter straining to complete a press in competition. Note chin is tilted down on his chest. Kono Photo.

Current protocols have the competition platform situated on a raised stage. Weight stands, and a chalk container are present on stage. No competition staff (loaders, medical, technical) are permitted on the stage when the athlete is called to the platform for an attempt.

Under these conditions lessons learned from Valsalva episodes of the press era seem to have been forgotten in the biathlon era. This loss of corporate memory can have ramifications of varying severity for a number reasons. The press is gone and with it prolonged straining, with its incumbent breath holding; all the while pushing a weight over the head. There may be fewer episodes or at the least fewer dramatic Valsalva episodes; nevertheless, they are still very common in weightlifting competitions.

In lieu of more precise physiological indicators, the following levels of impairment have been determined. These levels of impairment are arbitrary and of course conditional; but, nevertheless useful for practical application:

Level 1: minimal loss of motor control; athlete experiences slight dizziness;

Level 2: substantial loss of motor control/combined with dizziness causing the athlete to release the weight and drop to one knee, sit or lie on the platform;

Level 3: significant loss of motor control and dizziness; athlete drops or falls to the platform with modest spasms; the athlete may walk/run and/or begin falling backwards trying to gain equilibrium;

Level 4: cascading loss of motor control; extreme dizziness; the athlete struggles to remain conscious; usually drops uncontrollably to the platform;

Level 5: complete loss of motor control; loss of consciousness, cessation of breathing with possibility of cardiac arrest.

Figure 3. Coach catches collapsing athlete who is faint and has lost motor control at a competition without a stage. Coaches were able to stand on the same level and just a few meters from the edge of the platform. The coach’s proximity to the athlete and quick reaction to the situation may have prevented a serious injury. Jackie Charniga photo

Figure 4. Some lifters make an effort to take a deep breath and hold this before jerking the barbell. This can contribute and/or exacerbate a Valsalva episode in the jerk portion of the exercise. This athlete took a deep breath after struggling to stand from the squat. Soon after he began to pass out and had to drop the barbell. Charniga photos

Some specifics of Valsalva episodes:

- Most Valsalva episodes in weightlifting occur in the clean and jerk; especially after a difficult clean;

- Taking a deep breath before jerking the barbell can contribute to the possibility of a Valsalva episode;

- Barbell oscillation, especially with the 15 kg bar, in the most difficult portion of the recovery from the squat can contribute by prolonging strain;

Figure 5. Female lifters can experience excessive barbell oscillation through the most difficult range of the recovery from the clean; which in turn can prolong the straining and lead to a Valsalva episode. Charniga photo.

/ Cascading loss of consciousness/motor control vary with severity of episode;

/ There may be discreet differences between male and female episodes: males may experience more rapid, and/or a more debilitating loss of motor control;

/ Coaches and staff may react differently to a Valsalva episode with female and male lifters, i.e., think a female is just faint; or worse, overreact and proceed with iatrongenic measures.

Figure 6. Depending on the level of impairment resulting from a Valsalva episode the safety of the athlete necessitates a quick reaction. Jackie Charniga photo.

Some safety considerations to alter competition protocols:

-

- Rapid triage must be a priority;

-

- Some competition staff (loaders) must be situated on stage within several meters of the platform;

-

- Competition staff nearest the athlete should be aware of the signs of Valsalva episode and be ready to assist an athlete who may lose motor control;

-

- Expediency necessitates protecting (triage) the athlete from injury {supporting head and neck} in the event of complete loss of motor control;

-

- Medical personnel on duty should possess sufficient mobility to reach an athlete in distress quickly;

-

- Medical staff should be aware of the specifics of Valsalva in weightlifting so as to not overreact to an episode and be prepared to administer reasonable assistance;

- Medical staff and staff (loaders) nearest the athlete on the platform need to be on the same ‘page’, i. e., as far as the role played be each.

Figure 7. A gold standard of the effectiveness of providing reasonable safety precautions for the athlete. A Lifter suffers severe (level 4?) Valsalva episode after standing up from the clean at the 1962 World Championships. Loaders (no doubt lifters themselves) recognize the preliminary signs; run to support athlete who collapses uncontrollably to the platform. The loaders were able to reach the athlete before he comes to harm because they are situated on stage within a few meters of the platform.

Conclusions

Figure 8. A Valsalva episode can escalate to unanticipated severity. No one would expect a young healthy athlete could go into cardiac arrest from such an episode; nonetheless, it is in the realm of possibility. Charniga photos

Valsalva episodes are not a thing of the past in weightlifting competitions. Although the incidence and severity of Valsalva episodes resulting from straining to lift a weight overhead in the press belong to a bygone era in weightlifting; the lessons learned, have been forgotten in the biathlon era.

In point of fact, the current competition protocols with regards to athlete’s safety, are in some respects, an accident waiting to happen.

Medical staff on duty at competitions, however competent in medical matters, should not be the sole people charged with providing assistance. As the illustration in figure 7 from the 1962 world championships shows, practical experience is invaluable.

Furthermore, there is such a thing as iatrogenics, i.e., the treatment is more harmful than the disease. Doctors on duty need to understand even the worst of these episodes are over in a few minutes. Any medical protocols above and beyond protecting the athlete from injury from falling or striking head and/or injuring the neck are probably unnecessary.

Weightlifting is a sport of maximum strain. There are no compelling reasons, medical, legal or practical, lifters should be on a 4 x 4 meter platform, alone on a raised stage, with competition staff situated too far away to react in the event of a would be medical emergency. Under these conditions, a Valsalva episode, which could result in serious injury; could be averted where assistance nearby.

Videos or otherwise links were not posted on this article when it was first published in deference to any athlete who suffered such an episode. The reason being there are numerous incidences to be found in cyberspace where something like this is exploited to humiliate or make fun of a serious situation. However, since the below link has for some time been uploaded on Youtube for some time hopefully it’s educational value will supercede any harm that may have already occurred.

Several features of this incident illustrate vividly the need to have personal on the stage near the platform. Fortunately, the young woman was not injured but the fact remains the competition protocols are inadequate. In this incident the loading staff reach the athlete first, after she has hit the floor; to make a human curtain.

Link to Valsalva episode at 2015 Pan American weightlifting chps.:

/ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xaH-wY6egy4&t=190s

References

/ Yale, S., Clinical Medicine and Research

/Zatsiorsky, V. M., Science and Practice of Strength Training, Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL. 1995

/ Vorobeyev, A., N., Weightlifting, textbook for the institutes of sport, FIS, Moscow, 1988

/ Compton, D & Hill, P.Mcn & Sinclair, J.D., “Weight-lifters blackout”, Lancet. 2. 1234-7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(73)90974-4.